Alicja, 17, and Karolina, 16, review the prize-winning novel

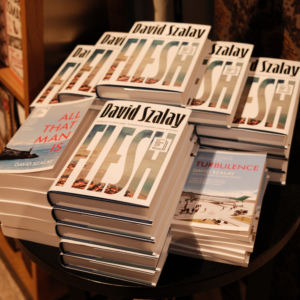

David Szalay’s prize-winning novel displayed at a bookstore in London.

Picture by: Harbingers’ Project

Article link copied.

20 January 2026

Written with bodily fluids, Szalay’s novel deserved the Booker Prize. Flesh review

The Booker Prize is one of the biggest and most respected literary awards worldwide. It is given each year to the best fiction novel — written in English and published in the United Kingdom or Ireland.

In 2025, the main prize went to Flesh, a novel by David Szalay, a 51-year-old Hungarian-Brition who grew up in London, in 2009 moved to Hungary, and currently lives in Vienna with his wife.

It was not the first time the committee recognised Szalay – in 2016, his fourth novel, All that a man is, was nominated to the prize, but ultimately he lost to Paul Beatty’s Sellout. This time, it was Szalay’s work that captivated the jurors.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

While some books are meant to comfort you, Flesh isn’t one of them. The story follows the life of Istvan, a simple Hungarian man, who comes across different obstacles in his life. And truth be told, the book doesn’t involve a lot of action — the protagonist simply allows his life to pass, and if not for the people he met, his life would be extremely not interesting.

Soon after starting the book, you can realise that Szalay created Istvan to be boring and ordinary – on purpose. It is a way to shift readers attention away from living, understood as being active, to what life means in terms of existence.

That’s where the novel shines: it explores all the conditions a human body can endure. Through orgasms, drugs, comas’, births and deaths, the author takes its readers for a journey along human life. Instead of describing ambitions, successes or choices, Szalay relates to the states everybody goes through: pleasure, devastation, sickness, exhaustion – you name it, and it is somewhere there. Istvan’s ordinariness makes the book feel realistic.

Genuinely, there is probably no book on this planet that has more „it’s okay” than Flesh. At the same time, it might be the most emotionally draining or uncomfortable novel you come across.

Dreadful experiences are narratively treated as casual, something that happened, making the reader at time feel the lack of empathy. However, this is another method to shift your attention from emotional meaning to the physical one — what has to be processed by the mind, in terms of facts is just something that happened to the body that, ultimately, every human is.

What makes Flesh striking is the boldness of the story. Shalay fully commits to his narrative premise by refusing to soften the events he presents, unwillingness to romanticise his characters and create an aesthetic feel to the book. Instead, he lets the authenticity of the novel flow through, focusing on confrontation and vulnerability rather than a compromises.

It is this unconventional approach that makes the book so compelling — it serves the question of what it really means to inhabit a human body, by using it as a metaphor of something not stable and constantly acted upon by external forces.

Another quality of Flesh is its stand-out originality. While countless literary works have explored the body, Shalay’s approach to the issue feels somehow fresh and unexpected. His systematic focus on what the body physically experiences is unexpected, allowing the reader to focus on an aspect of the story that doesn’t seem like a conventional point of view — the body is not shown simply as a vessel of the soul, through which we experience our lives, but in itself it is a site of conflict and transformation. Such narrative can provoke discomfort and unease in some, thus forcing reflection instead of passive consumption. It seems that might be the reason why this novel caught the attention of the Booker Prize judges — with its controversial format and risk-taking atmosphere, it appeals to readers and challenges them.

Nevertheless, the story is not without its weaknesses, as its at times graphic nature might feel overwhelming. It sometimes seems to cross the line between meaningful intensity of physical experiences to excessive descriptions that might seem even primitive. The relentless focus on the body leaves less room for emotional reflection, which appeals to some readers but drives others away. The repetition of descriptions of physical experiences can make their impact more dull, raising the question of whether the shock is a distraction that replaces deeper reflection. Shalay’s style is crucial for this disrupting effect. The language he uses is direct, deliberately uncomfortable, reinforcing the atmosphere of realness and confrontation. This surely enhances the novel’s message, but may feel almost suffocating.

Ultimately, Flesh succeeds in its aim to show everything that can happen to a human body. The narrative is extreme and risky, but somehow also appealing and compelling, with its meaningful ability to force the reader to confront the fragility of their own bodily experiences, as well as the limits of their physical existence. While the story is admired by some and resisted by others, it undeniably has a significant role in modern literature.

Written by:

Writer

HRB Film & Book Club

Warsaw, Poland

Born in 2008, in Warsaw, Poland, Ala joined Harbingers’ Magazine, excited to write about books, movies, tv and music.

At school, she’s focused on studying history and literature, and aspirers to connect these subjects with her future studies in psychology, sociology or law.

In her free time, she enjoys spending time outside – catching up with friends – as well as inside, mostly reading and adding movies to her watchlist. She loves art, music, film and photography, and she always looks forward to being inspired by a meaningful conversation.

Writer

HRB Film & Book Club

Warsaw, Poland

Born in 2009, Karolina joined Harbingers’ Magazine to write about her interests – cinema, culture, international affairs.

She is interested in business psychology and cinematography. In her free time she enjoys hiking, sailing and contemplating movies, as in her opinion a good movie cannot be equally liked by everyone.

Edited by:

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2026 The Oxford School for the Future